Until a few years ago, purple coneflowers, also known by their botanical name, Echinacea purpurea, were generally purple or mauve-pink. On occasion, you would see a white cultivar like ‘White Swan’ too.

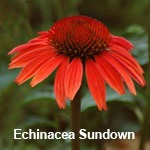

The traditional echinaceas are still around – with many improved cultivars on the market. But these days the newest cultivars are appearing in eye-popping shades of mango, orange and gold.

Unique coneflowers

Their new-look colors are making them the hottest must-have perennials of the season.

Native to North American prairies, as well as lightly-shaded woodlands, Echinacea produces showy, daisy-like flowers in mid-summer into the early fall.

The name “echinacea” comes from the flower’s spiky central cone – the Greek echinos means hedgehog.

The flowers are large and have big, dark cone-like centers. In the species, the petals often droop or curve back.

When the new-look mango, orange and gold echinaceas – most of them resulting from crosses between E. paradoxa and E. purpurea – were first introduced, they were in short supply and quite expensive.

That should change now that more varieties are on the market and growers have had time to build up supply. Look for them at your favorite garden center, or order them online.

New coneflowers

for your garden

Richard Saul of Itsaul Plants in Atlanta, Georgia, is one of the plant breeders in the vanguard of what he calls the “cone craze.” His claim to fame is the long-blooming Big SkyTM series:

Echinacea ‘Sunrise’ boasts fragrant four-inch wide lemon-yellow flowers that are held erect above multi-branched flower stalks. ‘Twilight’ has brilliant rose-red flowers.

Big Sky series Photo:

Courtesy of ItSaul Plants

Harvest Moon’ offers an attractive combination of four-inch wide fragrant flowers that have golden yellow petals surrounding a cone of golden orange.

The Big Sky cultivars are all hardy in USDA Zones 4 to 8. They grow about two to three feet tall, so space them about 15 to 18 inches apart.

Echinacea ‘Paranoia’ (shown below) is the result of a cross between the yellow-flowered North American native E. paradoxa and E. purpurea. The name comes from the champion of weird plant names, Tony Avent of Plant Delights Nursery, who made the selection.

Echinacea ‘Paranoia’

The flowers have pale yellow petals that curve down from a dark central cone.

The plant is sterile, so its flower-heads will not provide seeds for the birds. Grows 12 inches tall. Hardy in USDA Zones 5-8.

Echinacea ‘Fragrant Angel’ is a good choice if you are looking for large fragrant white flowers. This cultivar boasts double rows of petals that are held upright, not drooping, making the show even better. This cultivar is said to be hardy to USDA Zone 3.

Echinacea ‘Fragrant Angel’

Echinacea ‘Doubledecker’ (shown below) is new twist on the purple coneflower. Its odd two-tiered blooms that are sure to stop traffic.

The plant tends to produce some single blooms in the first season, but develops a high proportion of double-decker blooms in the second year. Grows about 30 inches tall; hardy from USDA Zones 3 to 9.

Caring for coneflowers

Echinacea ‘Paranoia’

Coneflowers thrive in full sun and most garden soils. They grow two to three feet tall, are easy to care for, and make wonderful butterfly magnets.

To encourage more flowers, deadheaded your coneflower plants regularly. You can also try shearing the plants back by half or two-thirds their height in early summer to encourage bushier growth and more profuse flowering later in the season.

Coneflower seed-heads are a favorite food of migrating and overwintering birds. If you leave the spent flower-heads in place in late fall, you will find that they are very good at attracting birds to your yard.

Coneflower cultivars are drought-tolerant, but their foliage and flowers can dry up in severe drought. Your plants will look more attractive if you water them regularly during very dry periods.

Try this method if you are not in a rush to plant, and you don’t mind looking at a pile of organic matter for a season. (This isn’t really a problem if the season in question is winter.)

You can start this project in early spring or in the fall – in either case, you’ll be ready to plant by the following spring.

More Information

Deadheading perennials – why and how

Introduction to prairie wildflower gardens

Resources for creating praire-style gardens